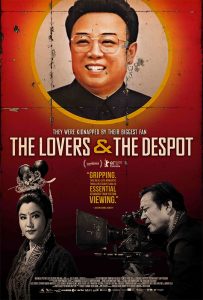

The Lovers and the Despot tells the story of young, ambitious South Korean filmmaker Shin Sang-ok and actress Choi Eun-hee, who met and fell in love in 1950s post-war Korea. In the 70s, after reaching the top of Korean society following a string of successful films, Choi was kidnapped in Hong Kong by North Korean agents and taken to meet Kim Jong-il. While searching for Choi, Shin also was kidnapped, and following five years of imprisonment, the couple was reunited in North Korea by the movie-obsessed Kim, who declared them his personal filmmakers.

Choi appeared in eighty-one films. She received the award for best actress at the 14th Moscow International Film Festival in 1985, for her part in the film Sogum.

DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT

We can’t remember exactly when we first heard this story. For a long time it seemed to reside in our imaginations as a possibly apocryphal tale concocted by a career fabulist. It seemed far too outlandish to be true – a director and an actress kidnapped by a brutal dictator to improve his films. Many directors and actors have led fascinating lives and had passionate love affairs, but none have experienced such a thrilling melodrama as Choi and Shin. As a film about filmmakers caught up in a narrative beyond their own making, it had particular appeal for us – as storytellers – in the possibilities of its telling.

For some time, we were sure that a story as good as this must have already been committed to film. But where was that film and why hadn’t we heard of it? Our interest grew as research revealed very little and we soon made a pact to clear our schedules and pursue this story wholeheartedly. We flew to Seoul with boundless optimism accompanied by a friendly British-born Korean interpreter and a carefully selected range of typically English teas, jams and other professionally wrapped gifts for Choi Eun-hee and the Shin Films Foundation.

Choi and her family representatives were always charming and gracious hosts, but they were understandably cautious about how their story would be presented. After two years of multiple lengthy trips to Seoul for extremely protracted and testing negotiations, in which we managed to fight off rival potential productions, we finally persuaded Choi, her son and her representatives that we were the ones to be entrusted with the task of doing justice to her and Shin’s amazing stories. Not being afforded the freedom to tell the tale in the way we wanted would have been the deal breaker for us. Ultimately, they realized that a biased or censored film would not help change the minds of those, especially in South Korea, who still believe they lied about their story.

Finding and securing a great story is one thing, but only one of our three main characters was still alive and we had only scant picture archive to represent any of them, so telling it was initially a huge challenge (alongside, of course, all the difficulties in raising a budget that a multi-lingual, expansive, internationally set narrative like this requires). We tried making contact with both North Korean representatives and the CIA, who we knew had extensively debriefed Shin and Choi after their escape, but both proved equally touchy. The former were unwilling to discuss anything involving the now highly taboo names of Shin and Choi and the latter wouldn’t even confirm or deny the existence of this obviously still classified case.

Eventually we managed to track down a curious selection of supporting players, such as a Hong Kong detective, an ‘off-the-record’ ex CIA agent, and an escaped former Court Poet to Kim Jong-il. Choi could tell her story, but who would tell Shin and Kim’s? Thankfully, some top-secret tape recordings came to the rescue. Shin had the foresight to realize that, should they ever escape, their story would be met with incredulity, so at great risk, he and Choi made recordings during their time in North Korea. Early on we had some excerpts of these, but it wasn’t until we got our hands on the rest of the tapes that we were able to get closer to our otherwise enigmatic protagonist and never-before-heard dictator. We had long been fascinated by the apparent Faustian pact that Shin entered into, and the conversations between Shin and Kim only deepened this aspect of the story for us. Was this a tale of a director’s ultimate temptation by the world’s most powerful producer or was Shin playing a masterful power game all along? Who was the master manipulator?

Besides the richness of the story itself and the exciting stylistic possibilities it offered in its telling, we were also drawn to the bizarre and still little understood world of North Korea and its leadership. Kim, even more so than other dictators before him, was fascinated by the medium of film as a means of influence and control – a weapon. Locked into the fantasy world of a paranoid state and raised in seclusion, it seems almost natural that Kim would be so compelled by the world of make-believe. North Korea itself is an extension of the Kim family’s grotesque and gaudy imagination, a perverse quasi-movie state where everyone must act their part on fear of death.

Kim makes for an intriguing villain – powerful, unpredictable, beguiling but ultimately a dangerous enigma who is a whimsical puppet master of our couple’s fates. Rather than another superficial portrayal of an evil dictator, the secret tape recordings afforded us the possibility to explore the motives behind Kim’s actions and hopefully gain a little more insight into a man who his captive, Choi, describes as intelligent, charming and fully aware of the peculiarities of the North Korean regime.

Kim Jong-il died in 2011, but his legacy continues in the longest running dictatorship of the modern era. Millions of North Koreans remain trapped within the ruins of his twisted psyche. Despite hopefully taking the audience on an entertaining thrill ride through Shin and Choi’s story, ultimately we felt we must leave them with a potent sense of the terrible reality that still exists in North Korea to this day, a reality from which few escape. Our protagonists and our Court Poet Jang are amongst the lucky few.