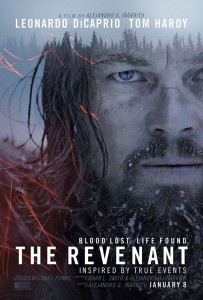

While on an expedition into the uncharted wilderness, legendary explorer Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) is brutally mauled by a bear, then abandoned by members of his own hunting team. Alone and near death, Glass refuses to succumb.

The film’s wilderness-based production mirrored the harsh conditions Glass and company actually lived through in the 1800s. Academy Award®-winning director Alejandro González Iñárritu and his whole cast and crew were up for all that was thrown at them, welcoming the challenges of shooting in Canada and Argentina, regions known for unpredictable weather and untouched wilds, in order to fully understand the experience of fur trappers in the early 19th century.

Glass himself left no writing behind, save a solitary letter written to the parents of a companion killed by the Arikara Indians. Since then, there have been biographies and novels – but in 2002, author Michael Punke published one of the most extensively researched accounts with The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge. The book was praised by Publishers Weekly as “a spellbinding tale of heroism and obsessive retribution” and became a favorite of readers who thrive on high adventure. Three of those readers included Anonymous Content producers Steve Golin, Keith Redmon and David Kanter. Anonymous Content enlisted Mark L. Smith to pen a screenplay. Smith saw in the story a chance to give people an experience we can barely imagine in our 21st Century technological lives.

Working with the cutting-edge Arri Alexa 65– the brand new large-format camera from the pioneering digital camera company –cinematographer, Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki utilized a range of wide lenses, spanning from 12mm to 21mm, to create extreme depth. The flexibility of the system lent itself to camera movements that often go from extreme close-ups to panoramas in synch with the film’s action, dreams and emotions. The team mixed three approaches — telescoping cranes, Steadicams and hand-held work – to allow Iñárritu to later sequence the visuals like a choreographer with Academy Award®-winning editor Stephen Mirrione.

New Regency was thrilled to work with Iñárritu. Says CEO and president Brad Weston: “We were fully committed to Alejandro’s vision – we understood the breadth and the scale of it and the need for flexibility and we saw it as a chance to get back to the roots of our company as a filmmaker-driven enterprise.”

“For over five years, this project was a dream for me,” says Iñárritu. “It’s an intense, emotional story set against a beautiful, epic backdrop that explores the lives of trappers who grew spiritually even as they suffered immensely physically. Though much of Glass’s story is apocryphal, we tried to stay very faithful to what these men went through in these undeveloped territories. We went through difficult physical and technical conditions to squeeze every honest emotion out of this incredible adventure.”

DiCaprio was also enthralled by Iñárritu’s aim to bring Glass’s story to life with a realism that would plunge audiences into life in primordial Western lands long before cowboys and outlaws. “I’ve never really seen this time period in American history put on film, so that interested me,” he says. “This was a unique time and place in the history of the American West because it was far more wild than what we think of as ‘the wild, wild West.”

The bear attack that threatens to end Glass’s life immediately took DiCaprio into a mano-a-mano struggle with one of nature’s most skilled predators. “The bear attack was incredibly difficult and arduous,” DiCaprio recalls, “but it’s profoundly moving. In the film, Alejandro puts you there almost like a fly buzzing around this attack, so that you feel the breath of Glass and the breath of the bear. What he achieved is beyond anything I’ve seen.”

DiCaprio did many of his own stunts: he was buried in snow, went naked in minus five-degree weather and jumped into a frigid river, each moment bringing him more in touch with Glass’s will. But as he makes his way, Glass does not just abide – he also changes profoundly, something DiCaprio reveals in a multi-hued range of subtle details that add up to the film’s stirring climax.

To portray Fitzgerald, who both betrays Glass and becomes his spark for enduring, Iñárritu cast the English actor Tom Hardy who has come to the fore in vastly contrasting roles, from the dream-world character of Eames in Christopher Nolan‘s Inception to the one-man tour-de-force of Locke.

Sixteen-year old Forrest Goodluck makes his big screen debut as Hawk, Hugh Glass’s fictionalized son by a Native woman. A member of the Diné, Mandan, Hidatsa and Tsimshian Native American tribes who lives in New Mexico, Goodluck endured a lengthy audition and rehearsal period to win the role.

To recreate this world in all its authentic shadings, Iñárritu recruited experts, including historian Clay Landry, who is affiliated with the only two U.S. museums devoted to the period: The Museum of the Mountain Man in Wyoming and Museum of the Fur Trade in Nebraska. Landry notes that among historians, the Hugh Glass story is Mountain Man 101. “If you study Rocky Mountain fur trade history, one of the first things you’ll learn is the Glass story. It’s that epic,” he muses. Throughout the production, Landry provided advice on trapper’s mindsets, tools and survival skills. He gave the cast a personal taste of all this in a “Trader’s Boot Camp” — where the homework included drawing bows, setting beaver traps, skinning [fake] beavers and throwing tomahawks.

As The Revenant begins, Captain Henry’s fur trapping expedition comes under attack from a band of tribesmen already settled along the banks of the Missouri River. These are the Arikara – dubbed simply the Ree by trappers — whose historic offensive against the Rocky Mountain Fur Trading Company would forever alter their fate. An oft-ignored yet integral part of Glass’s story, Iñárritu felt compelled to bring the Arikara’s presence to the fore in his telling of the tale. Known among their own people as the Sahnish, the Arikara were so named by other tribes for their feathered headdresses.

Shooting outdoors in Canada and Argentina, in snow, wind and often at high altitude, the cast and crew of The Revenant faced remnants of the same dangers and conditions that people living in the South Dakota region of 1823 would have faced.

Simply finding landscapes and weather raw enough to replicate the American West of 1823 was daunting. “It took five years to get the locations right,” Iñárritu explains. “I was very interested in the film presenting locations that hadn’t been touched by human beings so we searched for locations that would be almost that pristine. There was something pure and poetic about them.”