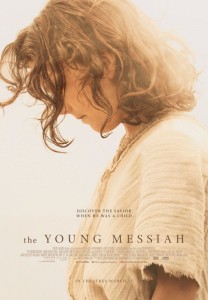

The inspiring and unique story of seven-year-old Jesus Christ and His family as they come to a fuller understanding of His divine nature and purpose.

To sing in selected places, the filmmakers brought in the well-known Jewish Roman choir Ha-Kol (meaning “the voice”), a group that was founded by singers of the Great Synagogue of Rome.

In 2005, Anne Rice wrote a fictional account of the childhood of a young Jesus Christ, entitled Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt. It quickly landed near the top of The New York Times bestseller list that year. Screenwriter Betsy Giffen Nowrasteh read the book when it was first released. “I was a fan of Anne’s books and was interested to see how she’d approach this material, and I loved it,” she says. The novel excited her so much that she even found herself giving the book to a number of friends, something she says she never does. She didn’t, however, immediately think of the book as a movie. It wasn’t until director and co-screenwriter Cyrus Nowrasteh (Betsy’s husband) received a call from the agent he shared with Anne Rice about the potential project several years later that the film adaptation, The Young Messiah, started taking shape.

Cyrus happened to be working with 1492 Pictures on another project. Betsy Giffen Nowrasteh recalls, “He was talking to producer Michael Barnathan, the usual chit-chat, and Cyrus mentioned that this book had been brought up.”

At the heart of The Young Messiah is a relatable tale about the struggle of a family trying to cope with a child who is realizing how very different he is from everyone else. Barnathan elaborates, “Anne said she chose this time period to write about because in human development at age seven, a human being starts to look inward. It’s the first time a child says, ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What am I going to be when I grow up?’ as opposed to ‘I’m hungry’ or ‘I’m cold’. It’s their first look inside, and this happened to coincide with the year the first King Herod died. ”

With 1492 on board as producers, Betsy and Cyrus got to work on adapting the novel for the screen – a process which didn’t come without challenges. The first was that the book spans a longer period covering several physical journeys for the holy family. The filmmakers believed that the movie version would benefit from being tighter. “It needed a ticking clock,” Cyrus says. “For it to be a movie, it really needed this drive to a conclusion.”

Rice has gone on record to say that Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt is her favorite book that she’s written, so the Nowrastehs were unsurprisingly nervous to hand over the script draft for her to read. “We showed her the script and she couldn’t have been more enthusiastic and effusive. It was a huge relief,” Betsy laughs. “For all of the changes we made, she saw that we understood the story. All the themes were intact and all the basic moves were from her material and the characters.”

“Whenever you have a child at the center of a movie, the greatest challenge becomes finding that actor,” says producer Michael Barnathan. “We had casting directors in the U.K., Italy, Jordan, Israel, the United States, and one that was looking everywhere else in the world. We knew that we had to find that child who instantly – by looking at him, hearing him – captures the innocence and the intelligence that the character should have. This is a child who is a product of God and man so the child had to be special, had to have a spirit in his eyes. You know it when you see it.”

Nowrasteh estimates that including self-tapes he looked at 2000 boys for the part. “Then I got a call from our casting director, Suzanne Smith in London, who told me that a little boy, Adam Greaves-Neal, had just walked in who made the hair stand up on the back of their necks.” Nowrasteh flew to London to meet with him.

Adam, just nine years old at the time he was cast, approached this monumental role the only way he could without feeling overwhelmed. He explains, “To me, I don’t think about it being ‘Jesus.’ I just think, I’m a boy that can do good and surprising things.”

With the role of the young Jesus finally cast, the filmmakers looked to the rest of the family. They started with Mary and Joseph. Sara Lazzaro, an Italian actress raised in both Italy and the U.S. was cast as Mary.

Lazzaro found herself immediately thinking, “How would people imagine Mary?” She notes, “I grew up in Italy and I have an art degree, so I grew up seeing all of the Madonnas. There’s a part of you that wants to fulfill an image of what people perhaps would like to see, but at the same time with the script I was entitled to step away from that.”

When it came to the casting of Joseph, Nowrasteh says that he always wanted to find a strong Joseph, something that traditionally hadn’t been portrayed before on-screen. He found that quality in Irish-born actor Vincent Walsh. “Joseph is the rock. He’s been misportrayed I think in a lot of movies in the past. He was just wallpaper; the guy hanging around pulling the donkey,” Nowrasteh laughs.

The next crucial casting decision to be made was for the newly written role of Severus, a character who was not featured in the novel. Severus is a Roman Centurion hired by Herod to find and kill the boy Jesus. Sean Bean, who had worked with 1492 Pictures on both Percy Jackson & The Olympians: The Lightning Thief and Pixels, was immediately drawn to the project from a historical perspective, as well as

to the complexity of the character of Severus.

When the filmmakers began discussing possible filming locations for this story, the central concern was being able to replicate the look of ancient Jerusalem and Nazareth. It became one of the greatest early challenges for the film. They scouted several different locations in Jordan, Morocco, and Israel before settling on Italy. “We knew that a number of Bible-themed movies had been shot in Italy,” notes director Cyrus Nowrasteh.

Production got underway in the southern Italian town of Matera. Producer Michael Barnathan was immediately taken with how the town resembled the historical locations in The Young Messiah. After The Passion of the Christ had been filmed there over a decade earlier, the city underwent a resurgence and tourism flourished.

When it came to creating the looks of the characters costume designer Stefano De Nardis and his department created over 1,400 individual pieces for the film.