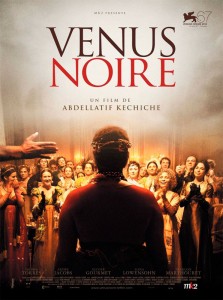

Black Venus (French: Vénus noire) is a French drama film directed by Abdellatif Kechiche. It is based on the life of Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman who in the early 19th century was exhibited in Europe under the name “Hottentot Venus”whose unusually oversized features brought her to 19th century Europe, where she found fame and fought for her own freedom. The film was nominated for the Golden Lion at the 67th Venice International Film Festival.

Black Venus is the story of Saartjes Baartman, a Black domestic who, in 1808, left Southern Africa, then ruled by Dutch settlers

Sarah “Saartjie” Baartman (before 1790 – 29 December 1815) (also spelled Bartman, Bartmann, Baartmen) was the most famous of at least two Khoikhoi women who were exhibited as freak show attractions in 19th century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus—”Hottentot” as the then-current name for the Khoi people, now considered an offensive term, and “Venus” in reference to the Roman goddess of love.

Sarah Baartman was born to a Khoisan family in the vicinity of the Gamtoos River in what is now the Eastern Cape of South Africa. She was orphaned in a commando raid. Saartjie, pronounced “Sahr-kee”, is the diminutive form of her name; in Afrikaans the use of the diminutive form commonly indicates familiarity or endearment rather than a literally short stature. Her birth name is unknown.

Baartman was a slave of Dutch farmers near Cape Town when Hendrick Cezar, the brother of her slave owner, suggested that she travel to England for exhibition, promising her that she would become wealthy. Lord Caledon, governor of the Cape, gave permission for the trip, but later regretted it after he fully learned its purpose. She left for London in 1810.

Baartman was exhibited around Britain, entertaining people by gyrating her nude buttocks and showing to Europeans what were thought of as highly unusual bodily features. She had large buttocks (steatopygia) and the elongated labia of some Khoisan women. To quote historian of science Stephen Jay Gould, “The labia minora, or inner lips, of the ordinary female genitalia are greatly enlarged in Khoi-San women, and may hang down three or four inches below the vulva when women stand, thus giving the impression of a separate and enveloping curtain of skin”. Baartman never allowed this trait to be exhibited while she was alive, and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, although apparently a tight-fitting one.

Her exhibition in London, scant years after the passing of the Slave Trade Act 1807, created a scandal. An abolitionist benevolent society called the African Association – the equivalent of a charity or pressure group – petitioned for her release. On November 24 1810 at the Court of King’s Bench the Attorney-general began the attempt ‘to give her liberty to say whether she was exhibited by her own consent’. In support he produced two affidavits in court. The first, from a Mr Bullock of Liverpool Museum, was intended to show Baartman had been brought to Britain by persons who referred to her as if she were property. The second described the degrading conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of coercion. Baartman was questioned before a court in Dutch, in which she was fluent, and stated that she was not under restraint and understood perfectly that she was guaranteed half of the profits. The conditions under which she made these statements are suspect, because it directly contradicts accounts of her exhibitions made by Zachary Macaulay of the African Institution and other eyewitnesses. On December 1 1811 Baartman was christened at Manchester Cathedral.

Baartman was sold to a Frenchman, who took her to his country. An animal trainer, Regu, exhibited her under more pressured conditions for fifteen months. French naturalists, among them Georges Cuvier, head keeper of the menagerie at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, visited her. She was the subject of several scientific paintings at the Jardin du Roi, where she was examined in March 1815: as Saint-Hilaire and Frédéric Cuvier, a younger brother of Georges, reported, “she was obliging enough to undress and to allow herself to be painted in the nude.” Once her novelty had worn thin with Parisians, she began to drink heavily and support herself with prostitution.

She died on 29 December 1815 of an indetermined inflammatory ailment, possibly smallpox, while other sources suggest she contracted syphilis, or pneumonia. An autopsy was conducted, and published by French anatomist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1816 and republished by French naturalist Georges Cuvier in the Memoires du Museum d’Histoire Naturelle in 1817. Cuvier notes in his monograph that Baartman was an intelligent woman who had an excellent memory and spoke Dutch fluently. Her skeleton, preserved genitals and brain were placed on display in Paris’ Musée de l’Homme until 1974, when they were removed from public view and stored out of sight; a molded casting was still shown for the following two years.

There were sporadic calls for the return of her remains, beginning in the 1940s, but the case became prominent only after Stephen Jay Gould wrote The Hottentot Venus in the 1980s. After the victory of the African National Congress in the South African general election, 1994, President Nelson Mandela formally requested that France return the remains. After much legal wrangling and debates in the French National Assembly, France acceded to the request on 6 March 2002. Her remains were repatriated to her homeland, the Gamtoos Valley, on 6 May 2002 and they were buried on 9 August 2002 on Vergaderingskop, a hill in the town of Hankey over 200 years after her birth.

Baartman became an icon in South Africa as representative of many aspects of the nation’s history. The Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children, a refuge for survivors of domestic violence, opened in Cape Town in 1999. South Africa’s first offshore environmental protection vessel, the Sarah Baartman, is also named after her.

Composer Hendrik Hofmeyr composed a 20 minute opera entitled Saartjie which premiered by Cape Town Opera in November 2010.