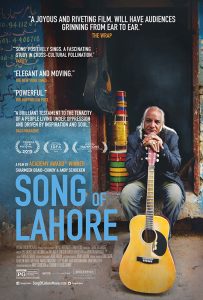

Song of Lahore,follows the members of Pakistan‘s Sachal Jazz Ensemble, a group of master musicians who find international recognition after decades of being forced underground by dictators and religious extremists.

Director Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy notes that there is no prohibition against music in Islam. In fact, there are many Islamic cultures that are very supportive of the arts. Rather, she believes, music is simply an easy target for extremists. “Music is the first line of defense. It’s so easy to silence music and it always creates headlines. It’s been used by people to manipulate the religion.”

When Academy Award-winning documentarian Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy first got the idea to chronicle the story of Pakistan’s Sachal Jazz Ensemble, she had no way of knowing the project would take her and the group on an exhilarating journey culminating with a triumphant performance in New York City. “In 2012 I came across the story of a group of musicians from Lahore who had

come together against all odds to record music using Pakistan’s traditional instruments and I knew that was a story I wanted to tell,” she recalls. “I just wanted to preserve their voices and their music. I contacted the founder, Izzat Majeed, and he was open to the idea and that’s how the project began.”

As she began interviewing the musicians, a number of especially compelling

personalities and storylines emerged. “It quickly became clear that I wanted to feature

arranger and conductor Nijat Ali. He has such an engaging personality and such an amazing relationship with his father. I also wanted to focus on Baqir Abbas, who plays the flute, which is beautiful, and guitarist Asad Ali, who’s sort of a hippie and has this vibe about him that’s very reminiscent of the 1960s and the life he led back then. I was also interested in Saleem Khan, the violinist who desperately wanted his grandchildren to learn to play the violin, and was afraid the music would die with him.”

Obaid-Chinoy had spent about a year interviewing ensemble members and filming rehearsals when the group received an invitation to perform with Jazz at Lincoln Center, Wynton Marsalis’ acclaimed orchestra in New York. At that point, realizing the film would span two distant continents, Obaid-Chinoy decided to enlist the help of an American-based collaborator. Through Daniel Junge, her co-director on the Academy Award-winning short Saving Face, Obaid-Chinoy was introduced to Brooklyn filmmaker Andy Schocken.

“I got a call from Sharmeen and she told me about the film and it sounded like a fascinating project,” says Schocken, who makes his co-directorial debut on Song of Lahore.

“A couple of weeks later I was on a flight to Pakistan.”

Although they had never previously met face to face, Obaid-Chinoy and Schocken quickly established a collaborative flow. “We had great respect and trust for each other creatively so the co-directing relationship totally worked,” says Schocken. “We took a very improvisational approach to dividing the labor. She had started a year before I joined the project so she spent more time in production than I did. The editing of the film took place mostly in New York, so I was more strongly involved with overseeing that part of the process.”

Despite these years of hardship—or perhaps because of them—getting the ensemble members to open up about their lives and struggles was not always easy. For his part, Schocken faced a major hurdle in not speaking the languages spoken by many of the film’s subjects. “When you’re making a documentary, the success of the film is totally dependent on creating an emotional rapport with the people you’re filming. Doing that through an interpreter is very challenging. Even in post-production, working with Urdu, Punjabi and English presents a lot of organizational challenges.”

The filmmakers faced other challenges as well. “In Pakistan we have electricity issues, noise issues,” says Obaid-Chinoy. “An interview that would take you 30 to 45 minutes anywhere else in the world would take you an hour and a half because by the time you set up, the electricity goes out, the generator sounds are too loud, children are crying down the alley. There was a whole host of issues.”

Some of Song of Lahore’s most dramatic scenes take place once filming moves to New York, during the run up to the November 22 and 23, 2013, concerts in Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater. The filmmakers bring us into the rehearsal room as the Sachal musicians, whose tradition does not involve reading or writing music, struggle to find their footing under the watchful eye of Marsalis and his world-class jazz ensemble.

Although some of the pieces were working better than others, there was a serious problem with the Sachal Jazz Ensemble’s signature piece: in that pressure-cooker environment, the sitar player couldn’t handle the melody of “Take Five.” “The day before the concert they brought in a new sitar player who had never played jazz before,” remembers Schocken. “All of a sudden he was going to be on stage with Jazz at Lincoln Center in front of thousands of people. No one knew until the very moment he played it what was going to happen.”

Despite their historic Lincoln Center performance, the musicians of the Sachal Jazz

Ensemble are still not stars in their native country. “They have a cult following and they’re

gaining popularity, but they’re not mainstream musicians yet,” says Obaid-Chinoy. “I think

it’s going to take a little bit of time.” The filmmakers hope Song of Lahore will help

Pakistani audiences appreciate the value of the region’s traditional music and prove that it’s something worth supporting.