Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, based on the acclaimed bestselling novel by Ben Fountain, is told from the point of view of 19-year-old private Billy Lynn (newcomer Joe Alwyn) who, along with his fellow soldiers in Bravo Squad, becomes a hero after a harrowing Iraq battle and is brought home temporarily for a victory tour. Through flashbacks, culminating at the spectacular halftime show of the Thanksgiving Day football game, the film reveals what really happened to the squad – contrasting the realities of the war with America’s perceptions.

In order to make sure that the production was able to create a professional football game that might have been played in Texas in 2004, the filmmakers set up a trip to the city to catch a Thanksgiving Day football game,” remembers Executive Producer Brian Bell.

The story is based on a novel that producer Rhodri Thomas at Ink Factory read eight months prior to its publication (it ultimately became a 2012 National Book Award finalist). “A friend of mine, a publisher, gave me the manuscript and said, ‘You’ve got to read this book. It’ll change your life.’ I read it on vacation and loved it. It was anti-war but very much pro-soldier which is something that moved me deeply. After some inquiries my co-producer Stephen Cornwell and I found ourselves in dialogue with Ben Fountain the novel’s author.”

“So the Ink Factory optioned the book in 2012,” says Thomas, “and developed it with Film 4, the film arm of the UK broadcast Channel Four. They’re incredibly supportive of cinema–they like to take risks and six months before its publication they took a risk on this material. Happily, the book was phenomenally well-received. We then started developing the screenplay. With that screenplay, in 2013 we began work with TriStar—in fact they came to us because Tom Rothman, who at the time was running TriStar, was a fan of the book, which had been published by then. When Ang Lee signed on, we were thrilled. What we didn’t imagine was that he was going to make it as a 3D, high frame rate spectacle, we embraced in an instant having been completely blown over by Life of Pi.”

Producer Marc Platt remembers receiving “a phone call one day from Tom Rothman, who said

that he had a very special project to be directed by Ang Lee and ‘we’re not quite sure how to push it up the mountain.’ Ang is someone that I’ve always held in the highest regard as a filmmaker—back in my years as a production executive and President of Universal Pictures we made a film together called Ride With the Devil. So the moment he said Ang Lee of course I was interested. ”

“The genesis of the novel,” says novelist Ben Fountain, “ began in 2004 during a Cowboys

Thanksgiving Day football game. This was three weeks after the general election when George W. Bush had beaten Kerry. I felt like I didn’t understand my country. Then, we had a bunch of people over at our house for Thanksgiving. We had the game on. Halftime comes and I’m sitting on the sofa. And everybody else gets up, ‘cause nobody watches the halftime show. But I stayed and started watching the halftime show—I mean really looking at it. And it’s very much the way I write it in the book: a surreal, pretty psychotic mash-up of American patriotism, exceptionalism, popular music, soft-core porn and militarism: lots of soldiers standing on the field with American flags and fireworks. I thought, this is the craziest thing I’ve ever seen. I wondered

what it would be like to be a soldier who had been in combat who gets brought back to the US and dropped into this very artificial situation. What would that do to your head?”

“Adapting the novel,” notes Stephen Cornwell, “was a big challenge. And like any adaptation, it evolved. One of the big questions was how to place Billy at the center of the story. How to find a way of creating this character whom, in the novel, engages the reader with his internal dialogue. How do you make that work cinematically?”

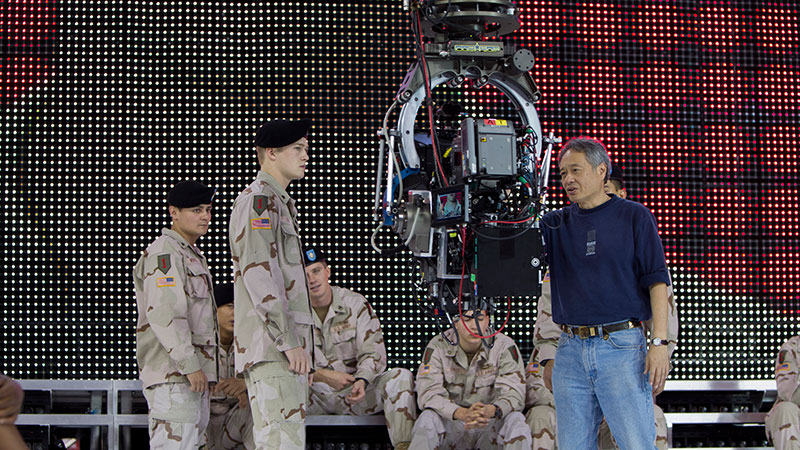

Ang Lee’s use of this new technology creates an immersive experience that is designed to allow

the audience to deeply experience Billy Lynn’s emotional, physical and spiritual journey in a

personal and profoundly encompassing way. “The film explores what the reality of his experience is for this one soldier, Billy Lynn; the technology allows us to realize how he hears it, how he views it,” notes Producer Marc Platt.

Lee’s approach would create logistical and technological challenges never before encountered on a traditional movie – the team developed a new cinematic lexicon by necessity, every shooting day and on into post-production, but always in service of the story. And his careful use of this new approach allowed him to explore shifts of dimension, film speed and perspectives with brand new tools. The movie even set up its own lab in Atlanta in order to process a vast quantity of data, as Lee and Toll invariably relied on two cameras running at five times the normal speed with twice the amount of data running on each of those cameras. That translated into twenty times the data storage of a normal high-quality Hollywood film on a daily basis.

Indeed, in order to achieve the 3D look, the positions of the two cameras on the rig must always match each other exactly. The cameras are physically bigger and sit on a rig that comes from a German company called Stereotech. Between the cameras is a mirror that’s half silver that allows us to overlap the cameras. The rig is run by motors, encoders and robotics that allowed Lee, John Toll and Demetri Portelli, the film’s sterographer, to manipulate the 3D depth. In other words, the team could shoot a 2D image as well as 3D, which occurs as soon as they start to separate the cameras. It allowed a huge range of flexibility in that they could choose the depth, essentially controlling how pronounced visuals were or how or how much they receded into the screen based on, among other things, Ang Lee’s sense of the emotional content for the scene.

The one big challenge is light because shooting at 120 frames means you need five times as much light. So the great challenge of the whole film is on DP John Toll to figure out how to work with so much light.

For the filmmakers, casting the right actor was crucial. “We searched and searched and

searched,” remembers Marc Platt, “ and many fine actors were tested and read. Ang knew what he was looking for, even though he didn’t know exactly what he was looking for. He kept turning over every stone—we saw actor after actor. One day when we were near a tape came from a young kid, Joe Alwyn, who was at university in London (the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama), and on his tape there was innate power, nuance and intuition that felt very much like the Billy Lynn we were looking for. So we brought him over to New York where he read and tested and the work spoke for itself. There was something about Joe that presented both the kind of blank slate that the film required Billy to be. ”

Joe Alwyn confides how “throughout the whole audition process it was hard to compute the

scale of it—this being Ang Lee and such a huge project. So when I was flown to New York to meet and audition for Ang I didn’t feel particularly nervous because in my head it was something completely other and so big that it didn’t kind of compute. So yeah, it’s a big one, I guess, to take on for the first-ever job. Coming from drama school and not having done any film work before, it’s taken some adjustment to be acting in a way that does not incorporate the entire arc of a journey over a few hours, as you would in a play. ”

The young actors’ bonding started before production. “It was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced, unlike anything that any of us had experienced or quite imagined that we would be going through,” remembers Joe Alwyn. “We were taken away for two weeks and put up into this kind of motel where we had to build our own bunk beds and stay and live 24/7. All access to the outside world was taken away from us, no phones or any form of communication. And then every morning, very, very early in the morning, we’d be taken off to this training camp in the woods run by former Navy seals who put us through our paces, to say it lightly, in terms of both physical and mental training. It was very hard, very intense.”

“Boot camp was something I was not expecting,” says Arturo Castro who plays Mango. “I knew it was going to be intense, I just didn’t know how psychologically and physically demanding it was going be. I didn’t expect them to treat us like this—normally actors get treated well,” he laughs.

The fictional town of Al-Ansakar, set in Diyala Province, was built amidst a cluster of small homes in a dusty section just outside of the city of Erfoud, Morocco. “We very much wanted to make sure that our scenery didn’t look like Hollywood,” says production designer Mark Friedberg, “so we needed to find a place where the background of the village preexisted and then built our part of the village. To make it all look authentic we worked with the people of the village to help us build our sets in their style, the way that they live. Part of the great violence of this battle is not just between the insurgents and our Bravos but how this beautiful, peaceful place is torn apart with 50-caliber gunfire explosions.”

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk was shot in native 3D and not in 2D with later 3D conversion. On set the filmmakers and crew wore special glasses to watch the 3D monitors; “Ang, who can see things dramatically in ways that other creatives don’t, insisted on shooting in 3D rather than converting for 3D,” says Scot Barbour, Vice President of Production Technology for Sony.