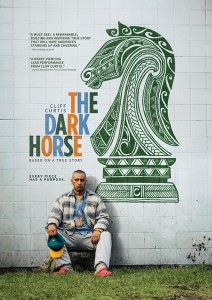

Based upon a powerful true story, The Dark Horse is the uplifting portrait of a man searching for the courage to lead, despite his struggles with mental illness. The film features a stunning, award-winning performance by Cliff Curtis as Genesis “Gen” Potini, a brilliant but troubled New Zealand chess champion who finds purpose by teaching underprivileged children about the rules of chess and life.

During his preparation for the role, Cliff Curtis had an opportunity to visit the community that Genesis had such a profound effect on: his hometown of Gisborne, New Zealand. Being welcomed into the chess legend’s circle of family and friends – including Gen’s wife Natalie and fellow Eastern Knights coaches Jedi and Noble – proved invaluable for the actor.

The filmmakers were first introduced to the inspiring true story of Genesis Potini in a documentary profiling the New Zealand speed‑chess player. The intimate film gave a true sense of the real man’s larger-than‐life persona, showing him coaching the Eastern Knights, trash‑talking his opponents and sharing details about his lifelong battle with bipolar disorder.

“When I saw Jim Marbrook’s documentary, I was instantly drawn in by Genesis,” says producer Tom Hern.

Hern immediately brought writer-director James Napier Robertson on board and arranged a meeting with Genesis. The Maori man welcomed the filmmakers into his home and opened up to them, speaking candidly about his past. “He was a natural, skilled storyteller,” Napier Robertson says. “He would talk about his mental illness and make very insightful, astute observations and analogies. I haven’t met anyone else that would think of explaining something to you in quite such a unique, engaging way.”

Throughout the writing and filming process, authenticity was writer-director James Napier Robertson’s driving principle; it was important to the filmmaker that the characters felt real and alive – because they were to him.

Genesis also applied this distinctive approach towards chess, which he believed was invaluable in shaping kids’ minds in a healthy, productive way. “He believed that the problem‑solving aspect of chess was a tool for life,” Cliff Curtis explains. “If you learned to look at any problem in life and to be strategic about your next move, these skills that you learned on the board were transferrable into real-‐‑ life situations.”

Robertson and Hern wouldn’t realize just how great of an impact Genesis had on the children of his community until the chess legend’s sudden death in 2011. “When we went to Genesis’s funeral, the room was overflowing with people. Principals brought in school kids who sang in his honor and people had sent messages from around the world. There were young men from all different walks of life who spoke about how Genesis had changed the course of their future through his mentorship and guidance,” says Napier Robertson.

By the time of Genesis’s death, the filmmakers had become close friends with the bighearted man and had received his blessing to tell his story. Says producer Hern: “The stakes of the project changed so much because suddenly there was pressure on the film to be a legacy for him.” Now more than ever, they knew that Genesis’s story needed to be told.

A crucial part of doing justice to Gen’s story was finding an actor who could fill the shoes of this remarkable man, nicknamed “Da Man” by his closest friends. The filmmakers knew the role would be challenging, requiring the actor to oscillate between bipolar highs and lows and capture both the heavy and light moments of Gen’s life.

“Genesis is a complicated character because he embodies so many contradictions,” producer Tom Hern explains. “He was a big beer‑drinking, toothless Maori man but he spoke like an accomplished orator and could easily feel as comfortable in the company of academics as he could with a street gang.” When Cliff Curtis first received the script, he was initially daunted by the role of Genesis and nearly turned it down. Thankfully, the filmmakers also shared the documentary with the actor, hoping to ignite the same spark they felt from watching it. Their tactic worked. After viewing it, Curtis was hooked.

Curtis, a New Zealand native, has carved a career as a prolific character actor. With his incredible range, director James Napier Robertson knew that Curtis could rise to the challenge of the role.

A crucial part of embodying Genesis was the physicality, Robertson felt. Gen was an imposing figure, weighing over 300 pounds with a shaved head and toothless grin. Curtis and the filmmakers decided the best way to approach the role was for Cliff to undergo a complete physical and mental transformation. The actor decided to go completely method and live as Genesis, an approach that neither the actor nor filmmakers had ever embarked on before.

“I dressed up as my version of Gen,” Curtis says. “I put my Crocs on, and put my gums in, and shaved my head, and drank a dozen to two dozen beers a day to help put on as much weight as I could. And it became comfortable to me.”

Going toe‑to‑toe with Cliff Curtis in such a commanding role was no easy feat for the supporting cast – particularly for Wayne Hapi, who had no prior acting experience before landing the conflicted role of Ariki. To help create such a convincing and captivating performance, Hapi drew from his own past experiences with gang life.

“We knew we had to find an amazing kid to fill the role of Mana,” director Napier Robertson says. Well known for his charming, humorous turn as the star in the popular Kiwi film Boy, James Rolleston was an obvious choice. But the filmmakers knew they would need to work closely with the young actor to coax out such a nuanced portrayal. “James was 15 years old when we filmed and he took the role extremely seriously,” producer Hern says.

To help the actors and the crew always feel connected to the film’s powerful main character, Napier Robertson asked the real Noble and Jedi to be on set every day. The two Eastern Knights coaches designed all of the speed‑chess games seen in the film and served as advisors, assisting the actors to become comfortable with the game. Their presence was also incredibly helpful to their actor counterparts, Kirk Torrance and Xavier Horan, who could get instant insight into the real friendships with their beloved Gen.

In honor of Genesis and the film, the Ngati Porou people of Gisborne wrote a haka, a traditional Maori song. Its powerful words help to capture Gen’s lasting legacy: “

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo.

You can praise them, disagree with them, quote them, disbelieve them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things.”