The Imposter is a classic American Gothic mystery revolving around crime, family, deceit and the slippery nature of truth – but it also really happened. That is why this riveting story inspired British filmmaker Bart Layton to push the non-fiction film into fresh territory: fusing the investigative spirit of a documentary with the breakneck pacing and atmosphere of a psychological thriller that hooks with its twists, turns and tantalizing questions of who to believe . . . and why.

Bart Layton worked closely with cinematographer Erik Wilson to develop the distinctive look of the film. “I had a vision for the dramatic sequences which incorporated ideas of memory, dreams and a kind of heightened reality full of atmosphere and conflicting color temperatures,” the director comments. “I’m not sure anyone other than my great and talented friend Erik could have helped achieve this in the same way.”

The film dissects both the tricky facts and emotions behind a shocking real-life case that began with a missing child, then unravelled into a labyrinth of hidden motives, brazen lies and deeper riddles. It started in June of 1994 when 13 year-old Nicholas Barclay was first reported missing from his home San Antonio, Texas, having never returned from an afternoon playing basketball with friends. He was a tough, street-smart kid from a troubled family and at the time, the media paid little attention.

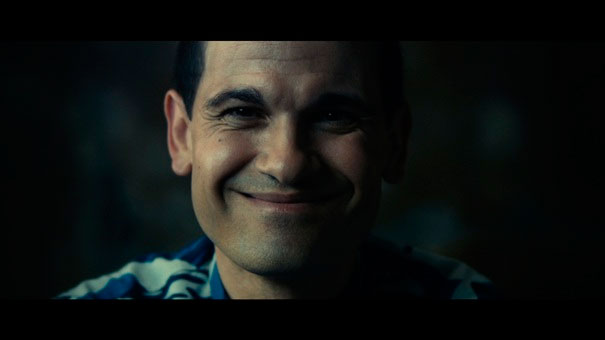

There are certain methods filmmakers typically use to tell a true story – but how do you tell a real-life story in which the truth keeps sliding out of your grasp? For Bart Layton, the story of The Imposter seemed to call out for the expressionistic structure of a taut, shadow-filled film noir as much as it did a straight-ahead documentary. Like a noir thriller, the story exposed the dark underbelly of an American dream, one rife with buried secrets, damaged innocence, doomed relationships and the sensation of being caught in a moral maze. The fact that real people had lived these events and were telling the story didn’t change that at all. If anything, their accounts deepened the mystery.

To that end, Layton wanted to give the film a style that would allow his real-life subjects to speak their own points-of-view — even as it revealed and undermined the illusion of reality running underneath. He chose to do so with his own inventive take on the dramatic re-creation. It proved to be the best cinematic tool to reveal the highly subjective, Rashomon-like memories that the Barclays and Bourdin offered of the real and fake Nicholases.

Layton’s re-creations openly break the mold because they are not meant to give the audience the straight facts (which didn’t exist in the Barclay case); instead, they are meant to lure the audience deeper into the fabric of the interviewees’ not necessarily reliable recollections. In that sense, they are more akin to “subjective visualizations” as Layton’s moody, creative photographic techniques make it clear that the filmmaker does not intend for the viewer to easily trust what their eyes are seeing.

“The hardest part was figuring out how to make sense of all the subjective and often conflicting versions of events described by each of the interviewees,” explains the director.